This Week In Debt: 11/3/2025

Blood and teeth, and banks.

Hello,

On some level, what caused the financial crisis in 2008 is that banks did a variety of bad things throughout the 1990s/2000s, and they did so specifically within their modality as consumer lenders. Oh sure, lots of other folks did bad things in that period too (credit rating agencies, specialty nonbank mortgage originators, list goes on), and banks also did bad or ultimately dumb things outside of consumer lending (become reliant on runnable short-term paper for funding, take on exposure to toxic mortgages that proved [i.e., the exposure] to be correlated, etc). But the banks were sort of at the center of the meltdown, and, after all, it was a mortgage crisis.

So when Congress set out to reform the financial system in response to 2008, a big slice of the changes it made took the general shape of Congress saying “we are going to put more guardrails on consumer finance, even if the banks (among others) tell us that our doing so will make them unhappy, and even if they say those changes will have net-negative trade-offs for consumers.” “Blood and teeth” and whatnot.[1]

For example, Congress created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). And the CFPB went on to do things like tell banks they couldn’t mislead consumers out of billions of dollars of interest payments.

These changes produced a lot of complaining. That griping took many forms, but one key line of complaint was that regulation had made it so unpleasant to be a bank that banks were (allegedly) either unwilling or unable to stay open. E.g.

And yet, Bloomberg reported this week that everyone now wants to be a bank (and you really must click through to see the graphic, which is a gif):

(Emphasis added throughout):

While the practice of fintechs pursuing [banking] licenses isn’t new, applications are rolling in at an increasing pace during President Donald Trump’s second term in the White House. According to a report from the Klaros Group, there have been 13 federal bank charter applications in 2025 as of Oct. 17, the highest total since 2020. Companies are capitalizing on what many business leaders see as a permissive regulatory climate under the new administration.

. . .

A bank charter can be attractive, especially for financial firms that need reliable access to cash, which deposits provide. Becoming a bank frees them from having to rely on banking partners to offer deposit services to customers. It can also offer access to deposit protection from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. as well as the Federal Reserve’s payment system, which enables efficient financial transactions.

The article goes on to talk about risks, with a nod to past disasters in non-banks becoming banks. (E.g., from the article, “In one of the best-known cases, GM’s financial arm, GMAC, needed a $17.2 billion bailout in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis after underwriting risky mortgages.” Oops!).

In parallel, the crypto world is having its own agita around banking. The recently-passed GENIUS Act brought stablecoins within the regulatory perimeter (including, if not exclusively, through banks). This matters in part because there are obvious ways in which stablecoins sort of walk and quack like uninsured bank deposits. The GENIUS Act aims in part to clarify that they are not, and it says that stablecoins can’t pay customers interest like deposit accounts do. And yet stablecoin issuers are doing exactly that, making interest payments and labeling them as “rewards” for stablecoin holders. Those rewards are now a flashpoint in efforts to pass a crypto “market structure” bill. The upshot is that crypto wants to have the advantages of doing the business of banking (such as offering consumers attractive interest payments on their deposits coins) without having the associated responsibilities (such as the horrible, unfair burden of taking basic steps to prevent terrorist financing).

I bring this all up to make a few points:

One way to look at the Bloomberg article is to say that companies are responding to deregulation. But you don’t have to see it that way—after all, notice that the article doesn’t actually quote saying saying “I got this charter because of deregulation,” or even like a market analyst confirming that people are doing that. It just sort of asserts that charter-seekers have deregulation in mind. And like . . . are those people just unaware that the mood could change? Is their plan to give up their charters if a Dem wins in 2028? Feels unlikely.

Instead, and particularly given the parallel crypto news, another way to look at the article is to say that it underscores how people/companies fundamentally want to be banks and do bank-like things, and how that desire remains present across administrations and regulatory regimes. They invent new ways to do it, they get bank charters, they don’t get bank charters, they find novel names for deposit products, the wheel turns. Nothing is new under the sun. But the desire to do banking shines through.

The thing you have to understand—the thing you have to repeat aloud until you correctly agree that it is the case—is that all banks are just private franchises of the government. They are private companies to whom the government grants the authority to engage in the public work of money creation. It is entirely reasonable for America and its states to condition their franchising of that power on compliance with consumer protections—even robust ones.

Banks are whiny. Fintechs are whiny and entitled. Throw crypto in with the latter.

Anyway, that was long. You want links! To the best stuff on the internet re: debt in the past week! Scroll down for precisely that.

So without further ado . . .

This Week In Debt: 11/3/2025

Let’s start in student loan land. First, the Trumps are trying to weaponize Public Service Loan Forgiveness.

The Trump administration released a final rule on Thursday that restricted who could participate in a student loan forgiveness program for public servants, making it easier to push out employers who engage in activities that it deems to have “a substantial illegal purpose.”

Those employers could include organizations that work with undocumented immigrants, for example, or provide gender-affirming care to children under the age of 19, among others.

The whole rule is here. Recall: Public Service Loan Forgiveness is a program that offers federal student loan borrowers debt cancellation in return for a decade of public service work, which has historically more or less meant work for the federal/a state/a local government or work at a 501(c)3 nonprofit. What’s going on here is that the Trumps are trying to narrow what constitutes public service work (i.e., to include only the stuff they like, and not, like, representing low-income immigrants in naturalization proceedings while working for a legal aid nonprofit). PB’s own Winston Berkman-Breen (in the article above) says it better than I can:

“This effort has always been about weaponizing debt relief to target and punish public service organizations and workers with whom the Trump-Vance administration disagrees,” said Winston Berkman-Breen, the legal director at Protect Borrowers.

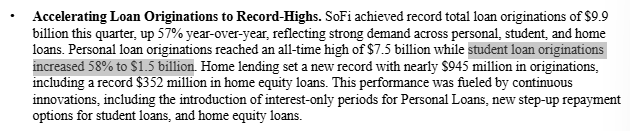

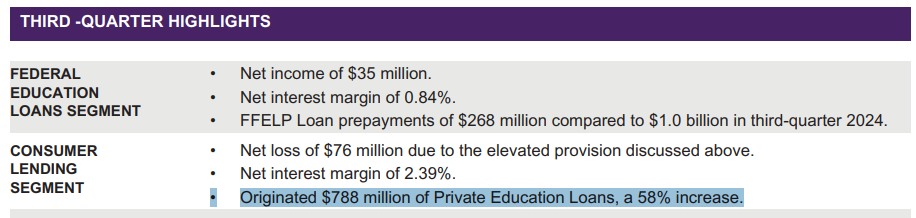

Meanwhile, private student lending is taking off, mostly in refi. (Recall: the PSL market basically consists of “in school” lending to students, and refinancing [“refi”] to people who have left school.) Some indicators:

SoFi: PSL originations (they only do refi and not in-school) are up 58%.

Navient: PSL originations are also up 58% (under the hood, in-school lending was up a bit, but refi doubled).

And remember that changes in the Big Bill (including limits on federal borrowing) are likely to increase in-school private student lending. Those changes haven’t taken effect yet. So man oh man, the fun/horror is just beginning!

Also, Sallie Mae changed its logo, and it looks like the Mondelez logo now, no?

The Trump CFPB is trying to block states from keeping medical debt off people’s credit reports.

Several states including Colorado, New York, and Maryland have passed medical debt reporting bans. But those laws are preempted by the Fair Credit Reporting Act and courts should overturn them, “consistent with Congress’s intent to create national standards for the credit reporting system,” the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau said in an interpretive rule set to be published Tuesday.

Recall a few things:

“Preemption” is when federal law blocks state law. The federal government has historically used preemption to (among other things) block states from protecting consumers. For example, in the lead-up to the 2008 mortgage crisis, the federal government used preemption under the National Bank Act to keep states from addressing predatory home lending.

The Biden administration issued guidance saying that the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which regulates credit reporting at the federal level, generally doesn’t preempt state laws on credit reporting. Then, the Biden CFPB published a rule that would have excluded medical debt from people’s credit reports. The rule arose from the observation that “medical debts provide little predictive value to lenders about borrowers’ ability to repay other debts,” that medical bills involve endemic errors, and that consumers are often “asked to pay bills that should have been covered by insurance or financial assistance programs.”

In the meantime, states passed their own laws banning medical debt from credit reports. As of last week, fifteen states had bans on the books.

Then things turned. First, in August, a court blocked the Biden-era medical debt reporting rule. Then, the Bureau released the guidance above, rescinding the Biden-era preemption rule and publishing a new rule saying that the FCRA does preempt state laws.

So we went from “states CAN regulate credit reporting and people’s medical bills CANNOT be part of their credit report” to “states CANNOT regulate credit reporting and people’s medical bills WILL be part of their credit report.” I, for one, am just glad we’re being governed by populists who have a deep respect for states’ rights.

Elsewhere: CFPB Revokes Rule Requiring Public Reporting of Non-Bank Enforcement Orders. I, for one, am just glad we’re being governed by conservatives who stand with [civil] law enforcement and believe that actions should have consequences.

(Emphasis added)

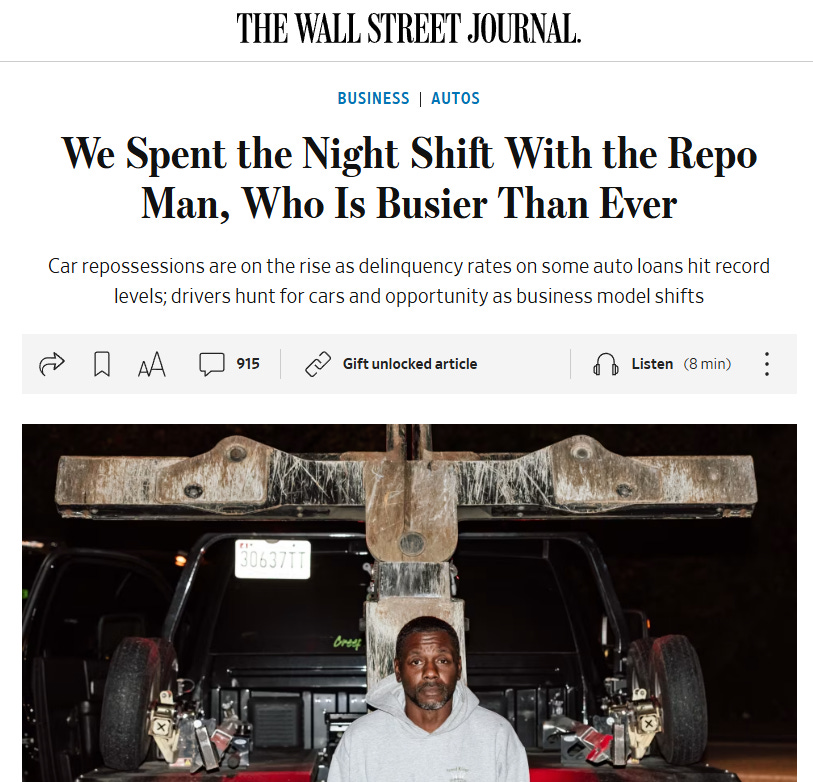

An estimated 1.73 million vehicles were repossessed last year, the most since recession-wracked 2009, according to automotive-service business Cox Automotive. There are signs the surge continues: This year’s repo volume at Cox’s Manheim auctions unit was up 12% through the end of September compared with the same period last year.

It is a rich text. E.g. (emphasis added): “The company collects cars around the clock, but the cover of darkness cuts the odds of encountering belligerent owners. As another slogan on the tow trucks says, ‘Creepin while you sleepin.’”

An update on how the other half borrows:

This article is about “box spread loans.” Matt Levine had a good explainer. Basically, a box-spread loan is really an options trade that (when the market behaves) produces a flow of funds that is economically equivalent to the trader getting and paying back a large loan with a super low interest rate. The article gives an example of someone borrowing $650k at 1.6% for 5 years via this trade, which is . . . a very good rate at which to borrow (emphasis added below):

Once a tool for hedge funds and family offices, box-spread loans now sit alongside direct indexing, custom portfolios, and options overlays — all pitched as tax-efficient ways to gain financial control. For affluent investors, they’re a means to stay invested, defer taxes, and unlock liquidity without touching traditional lenders.

. . .

In a box spread, two sets of options with matching strike prices — call spreads and put spreads — create predictable cash flows that closely mimic fixed income. By selling one, an investor receives a lump sum of cash upfront, and agrees to pay a preset amount at maturity. It’s a strategy that behaves predictably — until markets act up.

The gap between what the investor receives upfront and repays at maturity determines the effective interest rate — now roughly 5 to 20 basis points above comparable Treasury yields, according to Vest Financial, a $54 billion derivatives-based asset manager that officially launched its synthetic‑borrow platform this week.

Must be nice! However:

But the math only works if the market does. If stocks fall, so does the value of the collateral. That triggers margin calls — the same mechanism that has unraveled countless trades in past downturns. If the client can’t post more collateral, their portfolio gets liquidated. The promise of frictionless money becomes forced selling.

Elsewhere in Bloomberg: “Private Jets and Car Washes Are the Latest Tax Shields for the Ultrarich”

More private credit fallout/takes/stuff:

Bloomberg: “Private Credit’s Rising Pile of ‘Bad PIK’ Points to Default Woes”

WSJ: BlackRock Stung by Loans to Business Accused of ‘Breathtaking’ Fraud [involving private credit]

Natasha Sarin in NYT: How Bad Is Finance’s Cockroach Problem? We Are About to Find Out.

Art Wilmarth in Open Banker: The Next Financial Crisis Is Imminent, and Federal Officials Are Ignoring the Warning Signs (not just about private credit but)

Bloomberg reports on states’ rising efforts to go after Training Repayment Agreement Provisions (TRAPs) (featuring PB’s own Chris Hicks and PB Fellow Jonathan Harris!)

California passed a ban on TRAPs this year, and one in New York is on Hochul’s desk. The article also names Minnesota as a “prime candidate” to pass a ban.

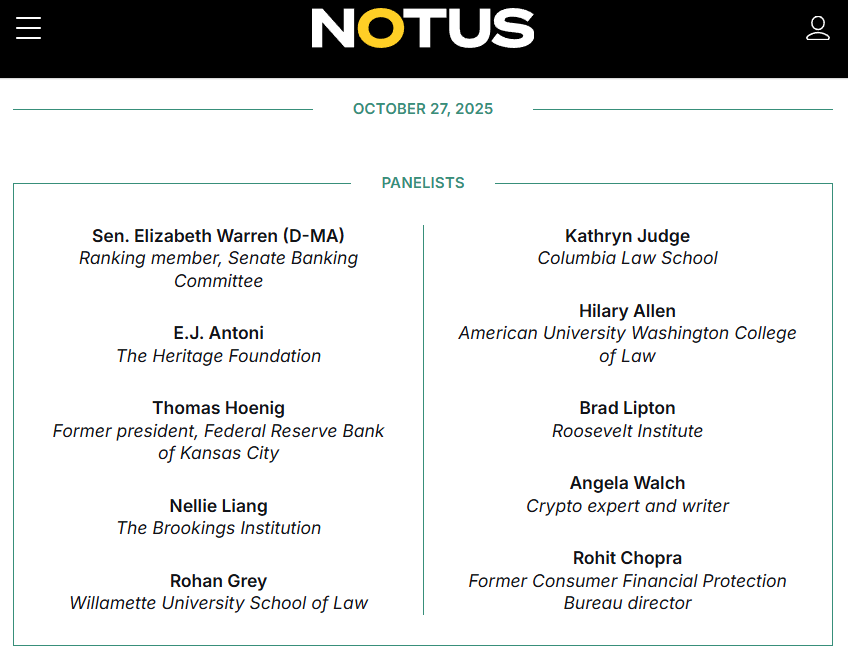

NOTUS (apparently the N is for “news”) had a very cool “forum” post asking various important people “What is the largest blind spot in current financial oversight?” Each person gave a little write-up with their answer.

Some of their answers:

Senator Warren: Trump is gutting the rules that prevent bank failures and protect our economy.

Tim Hoenig: The largest banks are over-leveraged, and the risks are massive.

Rohan Grey: Cash is under attack. The government needs to defend it.

Brad Lipton: The biggest blind spot is our collective illusion of economic calm.

Rohit Chopra: A dangerous lack of safeguards over uninsured deposits.

Every now and then, someone writes a profile of a young person that takes the shape of, “This person went to a fancy college and got a fancy lucrative job, then quit. Isn’t that interesting?” I followed that career path, any nobody wrote a profile about it, which truly must just be a skill issue. Anyway, Mother Jones recently did one of those profiles, and it made the rounds this week.

That’s really the pull quote?

And finally, here’s some potpourri:

Office CMBS Delinquency Rate Hits Record 11.8%, Much Worse than Financial Crisis. Multifamily Delinquencies Soar to 7.1%

Century Foundation President Julie Morgan on Adam Conover’s YouTube channel: How Trump Enabled the Rich to Steal from You

WSJ: The Economy That’s Great for Parents, Lousy for Their Grown-Up Kids

Bloomberg: Opioid Distributors Must Face $2.5 Billion Suit After Ruling

France is tightening restrictions on overdrafts.

WSJ: Barclays to Buy U.S. Lending Startup Best Egg for $800 Million

Billie Eilish to billionaires: “Give your money away, shorties”

Italy’s former culture minister to face ex-mistress in regional elections

Truck hauling monkeys [allegedly?] infected with hepatitis C, herpes and COVID overturns on Mississippi highway

Have a great week!

[1] Yes I know about the $10 billion supervisory threshold for depositories, etc, this is all simplified, roll with me.

The 58% jump in SOFI's PSL refi business is impressive, especially consideirng they're positioned primarily in refinancing rather than in-school lending. With the regulatory changes in the Big Bill likely to push more borrowers toward private lending, SOFI's growth trajectory could accelerate further.